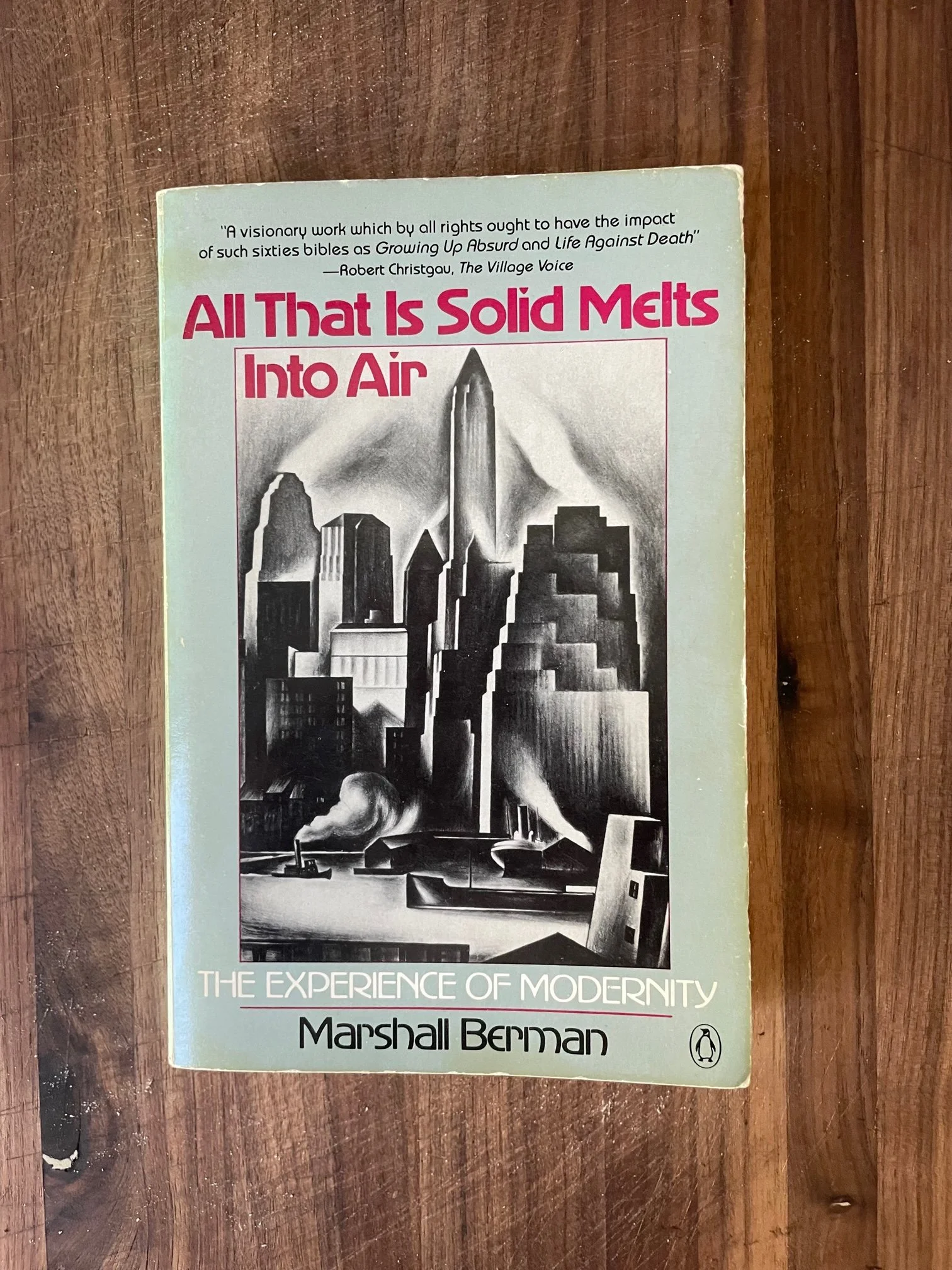

All That Is Solid Melts Into Air by Marshall Berman

“The argument of this book is that, in fact, the modernisms of the past can give us back a sense of our own modern roots, roots that go back two hundred years. They can help us connect our lives with the lives of millions of people who are living through the trauma of modernization thousands of miles away, in societies radically different from our own—and with millions of people who lived through it a century or more ago. They can illuminate the contradictory forces and needs that inspire and torment us: our desire to be rooted in a stable and coherent personal and social past, and our insatiable desire for growth—not merely for economic growth but for growth in experience, in pleasure, in knowledge, in sensibility—growth that destroys both the physical and social landscapes of our past, and our emotional links with those lost worlds; our desperate allegiances to ethnic, national, class and sexual groups which we hope will give us a firm ‘identity,’ and the internationalization of everyday life—of our clothes and household goods, our books and music, our ideas and fantasies—that spreads all our identities all over the map; our desire for clear and solid values to live by, and our desire to embrace the limitless possibilities of modern life and experience that obliterate all values; the social and political forces that propel us into explosive conflicts with other people and other peoples, even as we develop a deeper sensitivity and empathy toward our ordained enemies and come to realize, sometimes too late, that they are not so different from us after all. Experiences like these unite us with the nineteenth-century modern world: a world where, as Marx said, ‘everything is pregnant with its contrary’ and ‘all that is solid melts into air;’ a world where, as Nietzsche said, ‘there is danger, the mother of morality—great danger…displaced onto the individual, onto the nearest and dearest, onto the street, onto one’s own child, one’s own heart, one’s own innermost secret recesses of wish and will.’ Modern machines have changed a great deal in the years between the nineteenth-century modernists and ourselves; but modern men and women, as Marx and Nietzsche and Baudelaire and Dostoevsky saw them then, may only now be coming fully into their own.”

-Marshall Berman, 1982