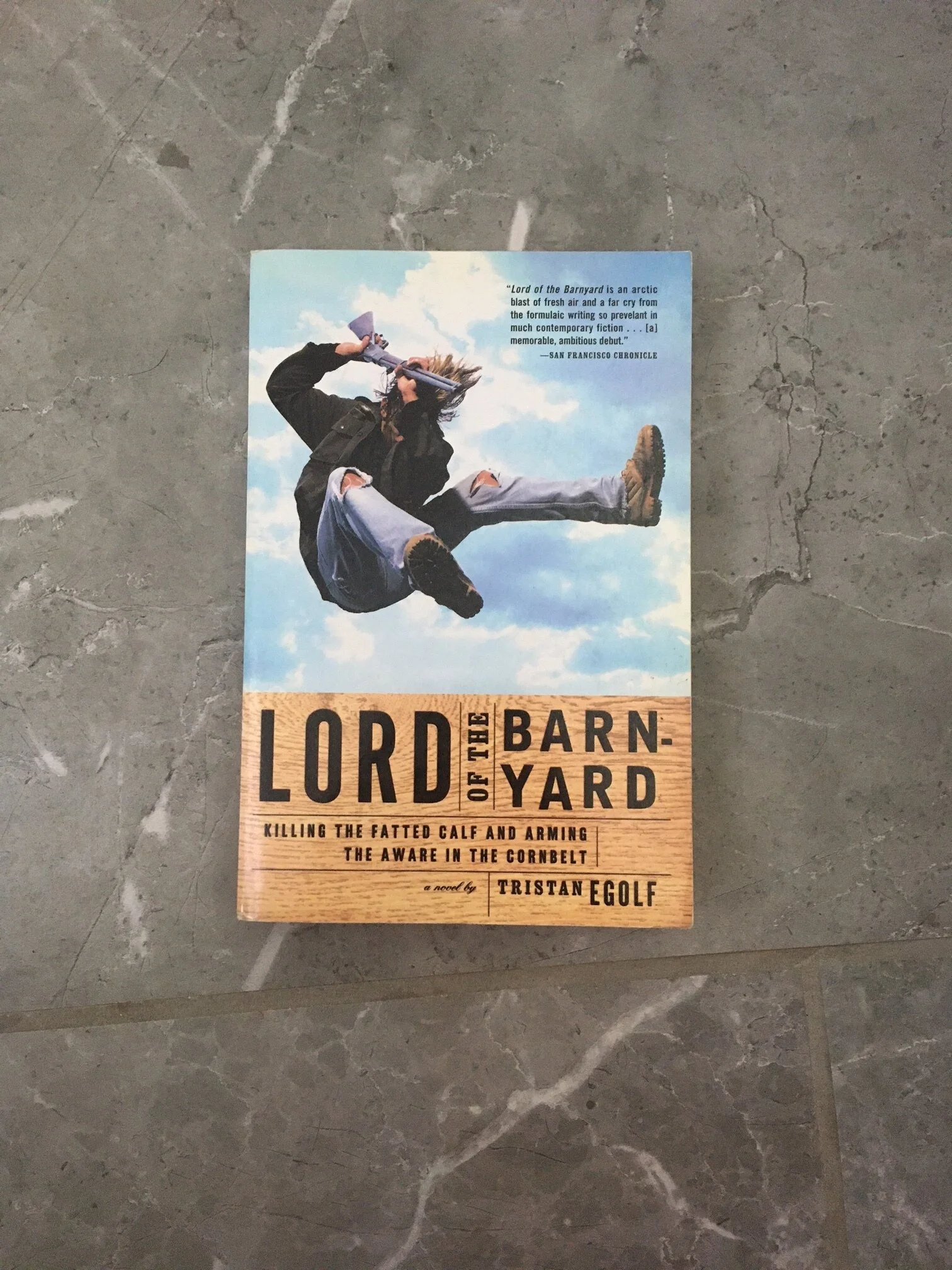

Lords of the Barnyard by Tristan Egolf

“But though the sheriff and his men, while creeping through the corn that afternoon, only expected to enact the routine round up of five or six inebriated juveniles, the scene they actually came upon in the middle of Bill Tulk’s field would remain with them as one of the most appallingly hideous spectacles they would ever encounter. Even now, years later, Tom Dippold is visibly shaken by the recollection of it. And it’s no wonder, most people would be, as, instead of discovering a handful of carefree, Schlitz guzzling yahoos in Cardinal jerseys as had been expected, the sheriff and his deputies pushed through the stalks and into the clearing to find no less than fifteen genuine, stoop-shouldered, hunchbacked, disease-ridden and massively deformed Patokah-side river rats seated around a flaming barrel, slobbering over scorched turkey remains. The ‘sick bastards’ hadn’t even bothered to remove the feathers from the bird. They were just tearing into the carcass with their fingers and holding raw chunks over the blaze until the skin had singed around the edges. Their faces and beards were mopped with sauce. They had wiped their hands on their already filthy, torn undershirts. The youngest of the lot, having seven or eight successive generations of inbreeding evidenced in the almost Cro-Magnon like contours of their skulls — the sloped foreheads, elongated jawlines, high-set cheekbones and cavernous eye sockets — were smeared in their own excrement and wrapped in soiled rag diapers that looked to have been left in place for the last two years. The whole clearing stank of death; anyone who’s ever been at close quarters with a river rat can only imagine. Anyone who hasn’t, can’t. The only comparative analogy that can be drawn is to say that for the sheriff and his deputies, it was much like being the local Avon lady sent to a cannibal camp on a daisy-plated delivery bike. It was the last thing they ever expected to encounter in their own jurisdiction.”

—Tristan Egolf, 1998